Accès libre Bibliothécaire Conférence Europe Histoire et sciences sociales Lettres

Notes de la conférence d’ouverture de prof. Alan Liu #DHN2018

Olivier Charbonneau 2018-03-07

J’ai l’énorme plaisir de participer à la Digital Humanities in Nordic Countries Conference à Helsinki cette semaine. J’y présente demain (jeudi après-midi) ma thèse doctorale, financée en partie par la Foundation Knight. Les thèmes de cette troisième version de cet événement sont: « cultural heritage; history; games; future; open science. »

J’ai l’énorme plaisir de participer à la Digital Humanities in Nordic Countries Conference à Helsinki cette semaine. J’y présente demain (jeudi après-midi) ma thèse doctorale, financée en partie par la Foundation Knight. Les thèmes de cette troisième version de cet événement sont: « cultural heritage; history; games; future; open science. »

Suivez la conférence sur Twitter grâce au mot-clic #DHN2018.

La conférence a été précédée par un séminaire sur l’utilisation d’outils de traduction simultanée dans le processus créatif. J’y reviendrai peut-être…

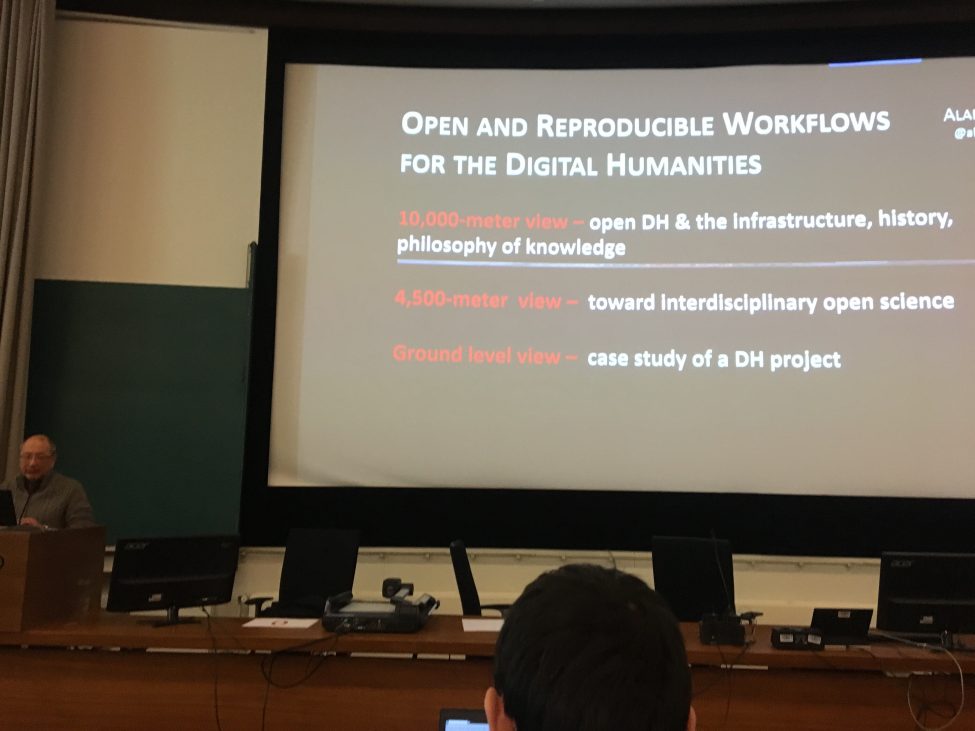

Je désire offrir mes notes de la communication d’ouverture du professeur Alan Liu, portant les protocoles de travail ouverts et reproductibles en humanités numériques. Il divise sa présentation en trois parties: la vue au rez-de-chaussée ; la vue à la cime des montagnes et la vue stratosphérique. Trois points de vue du même phénomène pour mieux saisir les défis à saisir.

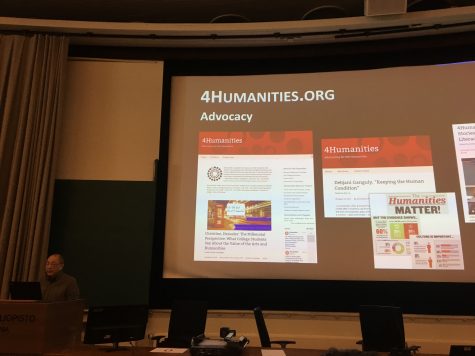

Avant tout, Liu définit les humanités en citant la loi habilitante du National Endowment for the Humanities aux USA (National Foundation for the Arts and the Humanities Act, 1965). En réalité, il articule « humanities » en cinq vecteurs théoriques: les humanities au sens classique platonique de la rhétorique, de la logique et de la grammaire; des social sciences; des science (au sens de STEM; et des creative & performing arts. Ces cinq vecteurs définissent les forces à l’oeuvre pour les humanités numériques. Il indique que les humanités sont essentielles dans le concert des disciplines intellectuelles, il collabore à l’initiative 4humanities.org pour en faire la promotion.

I. Vue du rez-de-chaussée

Prof. Liu présente son projet qui emploie l’outil DFR Browser pour son projet WhatEveryone1Says. Afin de proposer une méthode qui est ouverte et reproductible, Liu propose deux étapes, suivant cette structure:

A. Un système de gestion du cycle de vie virtuel (virtual workflow manager)

Utilisant un « Jupyter » notebook comme outil, l’équipe de Liu peut moissonner (scrape), gérer la provenance et le cycle de travail (workflow), les processus analytiques (analytical processes of topic modelling and word embedding), et l’interprétation. Sans le dévoilement de ces éléments, les humanités numériques ne peuvent espérer devenir une science ouverte et reproductibles.

B. Provenance

L’équipe de prof. Liu utilise des bibliothèques JSON pour l’identification du corpus et la confection de notes d’accès, les points de données (data nodes along the wy: raw data, processed data, scripts). Le tout est consigné dans une base de donnée MongoDB.

II. Vue à la cime des montagnes

Dans ce cas, il est essentiel pour un cycle de travail ouvert de se formaliser. Liu utilise « Wings » qui est une ontologie OWL. Il mentionne aussi le protocole W3C PROV (PROV-O; PROV-datamodel; PROV-OWL).

III. Vue stratosphérique

Liu cite la page 6 du rapport suivant: Our cultural commonwealth: Report on the American Council of Learned Societies on Cyberinfrastructure (2006). Liu cite aussi son rôle au sein de la nouvelle revue Journal of Cultural Analytics, basée à l’Université McGill à Montréal. Il cite aussi un article intitulé « Towards an automated data narrative » par Gil et al. dans Communications of the ACM.

Questions

J’ai posé la dernière quesiton à prof. Liu, à propos du rôle des bibliothèques et des bibliothécaire dans son « nouveau modèle » des humanités. Il précise que nous devons déconstruire le cycle de vie d’un projet pour identifier tous les microdocuments générés. Il faut aussi analyser les environnements numériques de travail: ceux de développement, de production, d’infonuagique. Il faut aussi bâtir des dépôts institutionnels et des dépôts de code informatique.

Accès libre

Journaux prédateurs

Olivier Charbonneau 2017-12-13

Le libre accès à la documentation scientifique est un sujet d’importance capitale pour les universitaires. Une des conséquence néfaste de ce movement vertueux consiste en l’émergence de journaux prédateurs, abusant du mouvement de la voie dorée de la publication en accès libre en lançant des journaux de piètre qualité simplement pour obtenir des frais de publication auprès de chercheurs désespérés ou étourdis.

Le libre accès à la documentation scientifique est un sujet d’importance capitale pour les universitaires. Une des conséquence néfaste de ce movement vertueux consiste en l’émergence de journaux prédateurs, abusant du mouvement de la voie dorée de la publication en accès libre en lançant des journaux de piètre qualité simplement pour obtenir des frais de publication auprès de chercheurs désespérés ou étourdis.

Comment savoir si un journal ou un éditeur pratique la prédation? Ce n’est pas évident. Permettez-moi de vous raconter l’histoire de Jeff Beall.

Ce bibliothécaire américain proposait une liste de journaux prétoires (ou, selon son site, « problématiques ») jusqu’à ce qu’il reçoive, ainsi que son université, une mise en demeure de la part de certains des éditeurs pour atteinte à la réputation (en droit, il s’agit d’une poursuite bâillon). N’ayant pas obtenu le support juridique adéquat, il a retiré sa liste d’internet. Depuis, il semble que la liste est maintenue par une source anonyme à cette adresse : https://beallslist.weebly.com/ (la source anonyme de ce site indique avoir diffusé une mise à jour il y a quelques semaines). La liste originale, à jour jusqu’en 2016, est archivée sur le site du Way Back Machine de l’Internet Archive : https://web.archive.org/web/20170111172309/https://scholarlyoa.com/individual-journals/ Le côté anonyme de cette source me gêne mais le contexte historique de celle-ci me rassure.

Certaines de mes collègues à Concordia ont travaillé la question des journaux prédateurs. J’ai pu discuter de la question avec l’une d’elles ce matin et elle m’indique que le site Internet des bibliothèques de l’University of British Columbia propose une excellente ressource sur la question des journaux prédateurs. Elles ont ajouté certains de ces élément sur notre propre site internet, dans la section sur le libre accès et les journaux prédateurs.

Source: Hall, Lake & Dennie. Choosing the right journal for your research: predatory publishers & open access, page visitée le 13 décembre 2017, http://www.concordia.ca/content/dam/library/docs/research-guides/political-science/GPLL234-predatory-publishing-FINAL.pdf

Par ailleurs, elles recommande le site http://thinkchecksubmit.org/. Non seulement est-il cité par les sites internet des bibliothèques de l’UBC et de Concordia, mais il est soutenu pour une impressionnante communauté d’associations reconnues du domaine de l’édition savante. Le seul bémol serait la dernière mise à jour de la section “what’s new” qui date de mai dernier… mais ça, c’est être pointilleux. Ce site est traduit en plusieurs langues, dont le français.

Journaliste Jugement Livre et édition Québec

Les nouvelles et l’utilisation équitable

Olivier Charbonneau 2017-09-28

Un collègue m’as mis la puce à l’oreille d’un jugement récent concernant l’utilisation équitable et la communication de nouvelles. Cedrom-SNI, La Presse, Le Devoir et Le Soleil ont obtenus une injonction interlocutoire contre un site qui moissonnait les titres et amorces d’articles afin de les rediffuser soit gratuitement son site, soit sous un abonnement payant. Voici le lien vers la cause:

Cedrom-SNI inc. c. Dose Pro inc., 2017 QCCS 3383 (CanLII), <http://canlii.ca/t/h50zb>, consulté le 2017-09-28

Je vous invite à lire ce sommaire de Julie Desrosiers, Chris Semerjian et Patricia Hénault chez Fasken Martineau. J’apprécie leur effort mais je suis un peu déçu qu’ils indiquent que cette « décision a de nombreuses implications dans la reconnaissance et l’étendue des droits d’auteur au Québec. » En fait, comme le précise le juge au paragraphe 23:

[23] Le Tribunal doit garder à l’esprit que le remède demandé est analysé en l’absence d’une preuve complète et qu’il doit éviter de se pencher sur la question comme s’il s’agissait d’un procès au fond. C’est ce que la Cour d’appel soulignait dans l’arrêt Morrissette c. St-Hyacinthe (Ville de)[9] :

Et, au paragraphe 48:

[48] (…) La question de déterminer s’il s’agit d’une portion importante du texte de l’article demeure une question pour le juge du fond.

À tout le moins, l’implication réelle de ce jugement concerne le recours aux injonctions dans un contexte de contrefaçon. Je ne veux pas minimiser la rigueur du travail de l’honnorable juge Duprat ou le travail des avocat.e.s travaillant sur le dossier. Je veux simplement contextualiser, pour le public, (et certains de mes lecteurs), les divers moyens procéduraux de la cour – tous les jugements n’ont pas le même poids. Il ne s’agit d’un prélude à une analyse plus approfondie de la question en droit.

Ceci dit, la conséquence pour le moissonneur de site de nouvelles est évident : il s’est fait couper l’herbe sous le pied (le jeu de motsest voulu). Sans source pour opérer son service et générer un revenu, il faut se demander s’il aura les moyens (pécuniers) pour se rendre à la prochaine étape…

Peut-être que d’autres seront de la partie ? Comme le précise le juge, encore au paragraphe 48:

Il faut soupeser le fait que ce type d’informations (titre et amorce ou simplement titre) est relayée en des millions d’occasions par des sites comme Google ou Yahoo.

Livre et édition Pétition Québec Utilisation équitable

Why I’m withdrawing from Copibec’s class-action suit against Université Laval (traduction)

Olivier Charbonneau 2017-09-22

(English post will start just after this blockquote.)

FR: Voici une traduction effectuée par l’Association canadienne des professeures et professeurs d’universités (dont je suis membre) du billet diffusé le 8 septembre 2017, intitulé « Pourquoi je vais me retirer du recours collectiv de Copibec contre l’Université Laval »

EN: This is a translation by the Canadian Associaiton of University Teachers (of which I am a member) of a post I wrote on September 8th on this blog.

As the author of published works, I qualify as a party to the class-action lawsuit brought by Copibec against Université Laval. That said, I plan to sign the opt-out form that will remove me from the class action and send it to both the registrar of the court and Copibec’s mailing address before October 15.

I’d like to put forward some of the reasons behind my decision, and which I hope will stand in support of Université Laval.

Before I continue, I invite the rest of the university community to join me in withdrawing from the class-action suit. All you need to do is complete the form provided on Copibec’s website and send it to the court clerk. The mailing address is on the form:

http://copibec.ca/medias/files/Action_collective/Formulaire-exclusion.pdf

I have two reasons for opting out: 1) the suit ignores the business realities of the academic setting and 2) it constitutes a severe breach of academic freedom and intellectual freedom, which are intertwined with freedom of expression.

1. Business realities of academic publishing

Despite Copibec’s complaints against Laval, in 2014-15, the institution spent $12.6 million on documents for its library, surpassed only by McGill University ($18.9 million).

Here’s a broader context: Quebec universities as a whole spent more than $63 million on library acquisitions, whereas the grand total for universities across Canada stands at $311 million. Public libraries in Quebec dished out roughly $30 million, and Quebec households bought more than $1 billion in books, newspapers and magazines. In 2012-13, more than two thirds of these expenditures (70% in Quebec) were for digital collections. What’s more, because digital sources now gobble up such a huge portion of annual acquisition budgets, the BCI no longer distinguishes between print and digital in its annual statistics.

The basic difference between a print collection and a digital one is easy to understand. Digital collections are acquired under a licence agreement that specifies usage rights, such as photocopying the material and sharing it with students through learning management systems. Print collections are governed by copyright law and by the licences of copyright-management collectives. Over the past few years, scientific publishers have in fact offered digital bundles for collections that institutions already have in hard-copy format—especially for scientific journals. Yes, university libraries have repurchased a significant portion of their existing print collections in digital format.

As a result, the proportion of print material(requiring a Copibec licence) of regular acquisitions is dwindling in the average Québec university library. In contrast, digital acquisitions, which require a licence similar to what Copibec offers, are booming. This new reality means that access rights, introduced by the Harper government in 2012 , are bundled, through licences, with digital works.

In fact, consumers of digital content are in the same boat: all platforms offering copyright-protected works in digital format always do so after having agreed to a digital licence. Reading a book on Kindle? You’ve said yes to Amazon. Same thing for Netflix, iTunes, Google Play, Steam… Consumers can simply glance over the terms of these licences but information professionals – your librarians, library technicians and clerks behind the scenes–well, they read and negotiate them on your behalf.

Let’s summarize the situation using the following equation, regardless of format or type of content:

Use = document + rights

In the print world, the equation was as follows:

Course packs sold to students = a university library’s print collection + Copibec licence

In the world of digital scholarly publishing, the reality that I experience and have studied is:

Use = digital document directly from the publisher + usage licence directly from the publisher

(Remember that libraries have transitioned to digital collections and acquire these in massive numbers.)

Note that without the publisher’s licence, it’s IMPOSSIBLE to acquire a digital resource. You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to understand that, for the average Quebec university, a licence with Copibec IS WORTH NEXT TO NOTHING. Why? Because the percentage of works offered in our licensed collections (that is, digital) is skyrocketing.

What’s more, I think Université Laval is one of the only Quebec universities to have done any rigorous “library economics” homework. All of the other universities in the province are passing along the cost of Copibec’s licence to their students, through ancillary fees, so they don’t see the urgency of challenging the current copyright orthodoxy.

If I were so bold as to summarize Copibec’s position, the fundamental equation for library-based access to works would be as follows:

Use = document comes from who knows where, and maybe from what’s left in the paper collection + copyright infringement through the fair dealing exception.

This assertion comes from a fairy tale that doesn’t reflect what I experience at work every day. My doctoral research, based on empirical analyses, confirms what I’m seeing at work.

Indeed, resorting to the principle of “fair dealings” is itself an exception, and to get back to the rocket-scientist analogy, a diligent and reasonable rights holder would immediately grasp its clients’ interest for digital material and put forward a palatable solution… Digitizing a work costs money. Consider all of the universities that digitize works on the fly to tap into the concept of fair dealings as an exception to copyright. The copyright holder could digitize everything in one fell swoop and sell the same copy to every university … around the world! That’s one of the secret formulas of the world’s biggest academic publishers.

If the Canadian government adopted a full slate of exceptions in the 2012 Copyright Act, it also assigned a new right to rights holders: making material available online. Quebec’s universities, especially Laval, diligently kept pace with the world of academic publishing in embracing digital formats. I don’t think Laval is at fault here, but I do think that Copibec, in reality, is defending a sort of commercial sloth. In addition, I believe the cultural sector is transposing its own reality on that of academia. The market failures and externalities of one sector are not the same as in others, even though copyright governs them all.

In fact, it would be more relevant to consider fair dealings as the public sector’s investment in mastering the workings of the markets and of the social systems generated by the digital world. University libraries, together with professors, students, techno-educators and other partners, are analyzing the needs of their clienteles and are trying to establish economic and social systems around digital works. We then transfer this knowledge to the industry through negotiated licence agreements or through exceptions. In both cases, opportunity knocks for whoever understands the message and adjusts accordingly. Copibec should put forward a business deal that considers our needs—suing libraries points to a woeful misunderstanding of the powerful trends affecting university markets and the academic publishing sector.

What happened to the horse when the automobile was invented…? Darwin and Shumpeter can shed some light on that.

This isn’t only my professional assessment of the situation, but also the conclusion of my doctoral thesis (which I’ll be defending on September 15).

2. Academic and intellectual freedom: integral parts of freedom of expression

I developed the link between academic and intellectual freedom and freedom of expression in a book chapter dealing with open access, available at Concordia University’s Research Repository, and which was published in the Handbook of Intellectual Freedom. All of the authors of this work won awards for their contributions from the Intellectual Freedom Round Table of the American Library Association. Here is an excerpt from my chapter:

There is a clear consensus in the literature that intellectual freedom is directly linked with freedom of expression, the press and to access and use information and that it is a core value of librarianship. Gorman famously stated that:

“In the United States, [intellectual freedom] is constitutionally protected by the First Amendment to the Constitution, which states, in part, ‘Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging freedom of speech, or of the press.’ There is, of course, no such thing as an absolute freedom outside the pages of fiction and utopian writings, and, for that reason, intellectual freedom is constrained by law in every jurisdiction.” (2000, p. 88)

Gorman continues to state that rarely are proponents “for” or “against” intellectual freedom, but they articulate their views in absolute or relative terms. On these issues, Hauptman (2002 pp. 16-29) as well as and McMenemy, Poulter and Burton (2007) offer additional evidence and insight. The link between intellectual freedom and censorship is obvious.

Intellectual freedom is also linked with Article 19 of the United Nation’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states:

“Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” (1948)

Samek (2007, pp. 9-11) provides an account of how various groups, such as United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) have further articulated the concept of intellectual freedom in various initiatives and declarations.

Barendt offers an interesting distinction between academic freedom, a well-known right professors enjoy in universities, and intellectual freedom:

“[a] cademic freedom is not identical to intellectual freedom or to freedom of the mind. Intellectual freedom is a right to which we are all entitled, wherever we work. Like freedom of speech or expression, it is a general right belonging to all citizens.” (2010, p. 38)

In discussing how intellectual freedom and freedom of expression are intertwined, Krug further articulates, in light of librarianship, that:

“All people have the right to hold any belief or idea on any subject and to express those beliefs or ideas in whatever form they consider appropriate. The ability to express an idea or a belief is meaningless, however, unless there is an equal commitment to the right of unrestricted access to information and ideas regardless of the communication medium. Intellectual freedom, then, is the right to express one’s ideas and the right of others to be able to read, hear or view them.” (2006, p. 394-5)

From these points, we can draw a common thread for intellectual freedom, namely that it is universal in enshrining our right to access and use information. In light of this, intellectual freedom intersects or overlaps with open access in that the former is promoted as a way to maximize or optimize access to and use of digital documents and information, while the latter expresses a fundamental right of the same vein.

I believe that Copibec’s suit, despite its legality from a strictly legal point of view, illegitimately and inordinately undermines our fundamental rights.

3. Supporting statistics

—In 2014-15, Québec universities spent just under $70 million on library acquisitions (source: BCI).

—Canadian university libraries spent more than $311 million on acquisitions (source: CARL/ABRC 2014/15).

—In comparison, Québec households spent $657 million on books ($3 billion across Canada) and $417 million on newspapers and periodicals (just under $2 billion across Canada) in 2015 (source: Statistics Canada. Table 384-0041 – Detailed household final consumption expenditure provincial and territorial – annual (dollars)) CANSIM (socioeconomic data base). Site consulted on September 7, 2017.

—Percentage of acquisitions in digital format: 2012-2013 was the last year in which the library sub-committee of the Bureau de coopération interuniversitaire distinguished between digital and print acquisitions, with roughly three quarters of expenditures going to digital at the time. That proportion has increased steadily since (take my word for it, a librarian with more than 14 years’ experience).

4. Sources

Barendt, E. M. 2010. Academic freedom and the law: A comparative study. Oxford; Portland, Or.: Hart Pub.

Gorman, Michael. 2000. Our enduring values: Librarianship in the 21st century. Chicago: American Library Association.

Hauptman: forward of Buchanan, Elizabeth A., and Kathrine Henderson, eds. 2009. Case studies in library and information science ethics. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co.

Krug, Judith F. 2006. Libraries and the Internet. Chap. 7.3, In Intellectual freedom manual, ed. Office for Intellectual Freedom. 7th ed., 394. Chicago: American Library Association.

McMenemy, David, Alan Poulter and Paul F. Burton. A handbook of ethical practice: a practical guide to dealing with ethical issues in information and library work. Oxford: Chandos, 2007.

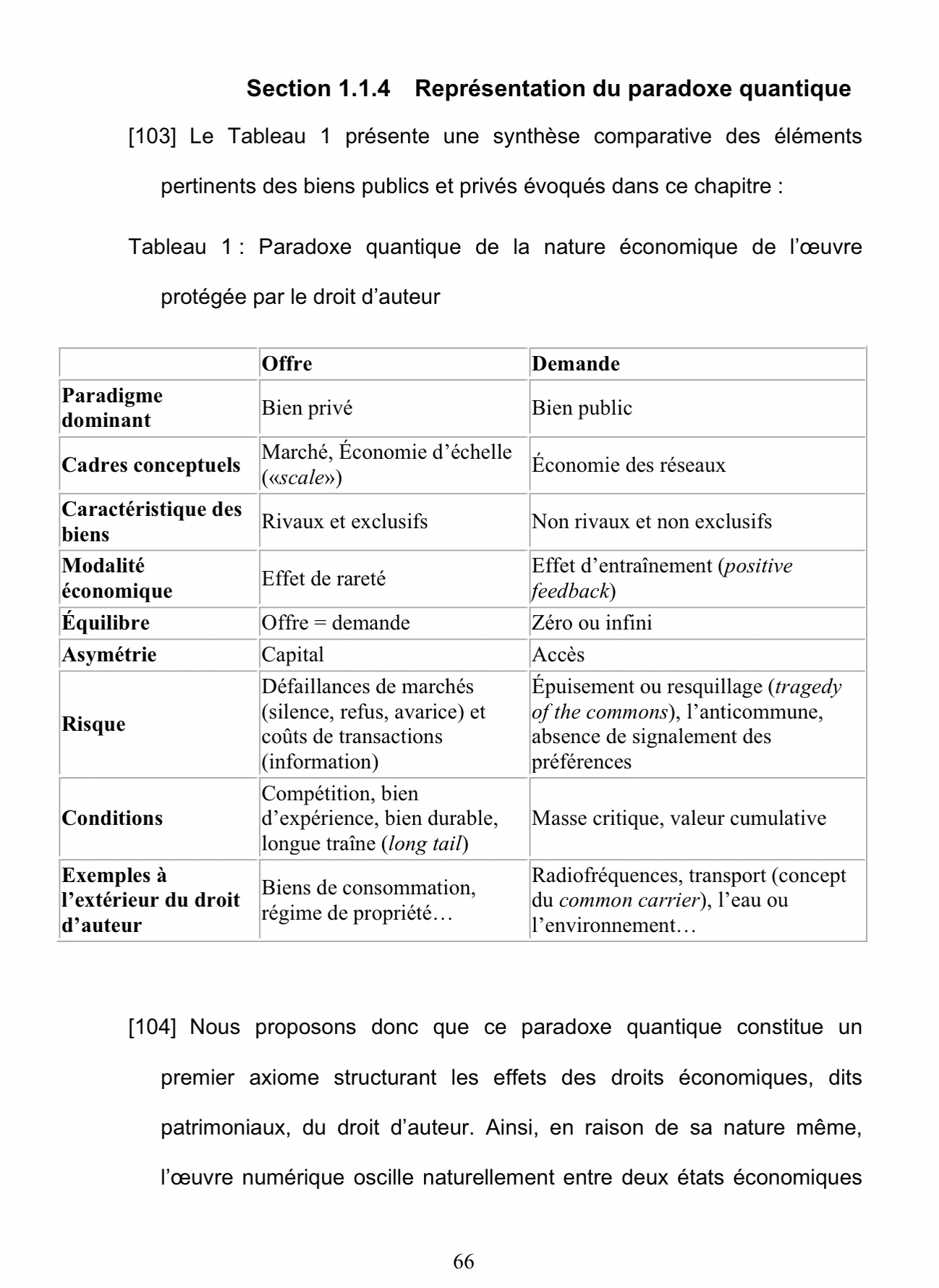

Samek, Toni. 2007. Librarianship and human rights: A twenty-first century guide. Oxford, England: Chandos.

J’ai l’énorme plaisir de participer à la Digital Humanities in Nordic Countries Conference à Helsinki cette semaine. J’y présente demain (jeudi après-midi) ma thèse doctorale, financée en partie par la Foundation Knight. Les thèmes de cette troisième version de cet événement sont: « cultural heritage; history; games; future; open science. »

J’ai l’énorme plaisir de participer à la Digital Humanities in Nordic Countries Conference à Helsinki cette semaine. J’y présente demain (jeudi après-midi) ma thèse doctorale, financée en partie par la Foundation Knight. Les thèmes de cette troisième version de cet événement sont: « cultural heritage; history; games; future; open science. »