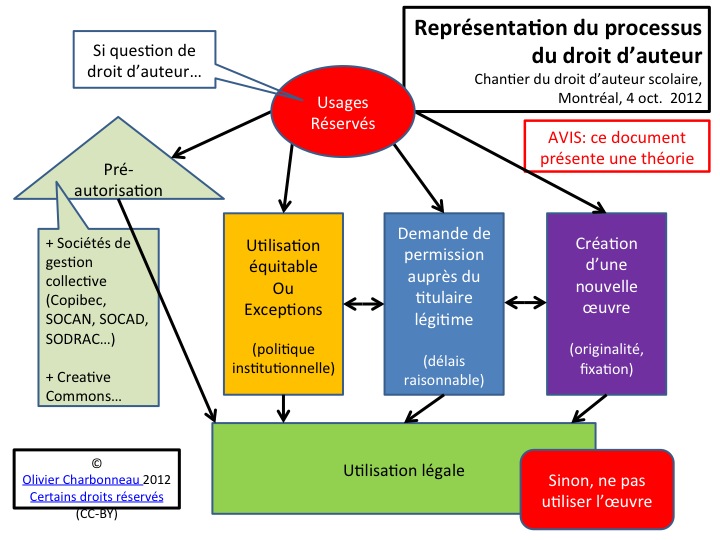

Beaucoup de choses changent dans la loi sur le droit d’auteur. On note l’émergence d’un nouveau droit – celui de mettre à disposition par Internet. Le législateur Canadien inclut aussi l’éducation, la parodie et la satire dans l’utilisation équitable. Il protège de sanctions criminelles tout bris d’un verrou numérique. Les institutions documentaires ont du pain sur la planche!

1

Copyright Fair Dealing Guidelines

______________________________________________________________________

Introduction:

University of Toronto faculty, staff and students are creators of material that is subject to the protections of the Copyright Act. They are also the users of such material. Accordingly, all have both rights and obligations that arise from copyright law as it has been interpreted and applied by the courts.

As specified in the Act, “copyright” in relation to a particular work means the sole right to produce or reproduce the work or any substantial part of it, to perform the work or any substantial part of it in public, and if the work is unpublished, to publish the work or any substantial part of it. Copyright extends to other activities such as adaptation, translation, and telecommunication to the public of a work. The definition in the Act also contains several other details that will not be explored here.

In general, if a work meets the definition of a copyright-protected work, copying the work or any substantial portion of it, or engaging in any of the other protected activities, will require permission of the copyright owner unless one of the exceptions in the Act applies. The statutory concept of “fair dealing” is an important exception, particularly in the educational context of a university, and these Guidelines will explain that concept and indicate the kinds and levels of copying that it typically includes. The Act also contains other specific educational exceptions that may apply to your activities. These will be covered in an update to of the University’s Copyright FAQs document, which will be published shortly.

Fair Dealing:

The fair dealing provisions in sections 29, 29.1, and 29.2 of the Copyright Act permit dealing with a copyright-protected work, without permission from or payment to the copyright owner, for specified purposes. These purposes are research, private study, education, parody, satire, criticism, review or news reporting. According to the Supreme Court of Canada the fair dealing exception is “always available” to users, provided that its legal requirements are met. When these legal requirements are met there is no need to look further at the more specific exceptions that follow in the legislation. Fair dealing, therefore, has considerable significance as people contemplating copying or other dealings with copyright-protected works consider what options are available.

“Fair dealing” is not defined in the Act. The concept has evolved significantly over the last decade through case law, including at the Supreme Court level through cases such as CCH Canadian v. Law Society of Upper Canada in 2004, and Alberta (Minister of Education) v. Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright), and Society of Composers,

2

Authors and Music Publishers of Canada v. Bell Canada, both in 2012. These decisions set out a multi-factor analysis for assessing whether a particular copying activity or other dealing falls within the ambit of fair dealing.

These Guidelines set out a short-form guide to assist in decision-making about copying. The University is of the view that these short-form Guidelines should provide a “safe harbour” for a considerable range of copying that occurs in the teaching and research activities of members of our community. However, in situations of doubt reference should be made to the underlying principles as articulated by the courts and specialized advice should be sought.

A) A Step-by-Step Approach to Determining if the Copying or other Dealing is Permitted :

The following sets out four steps, each of which needs to be considered before you copy material for teaching or research purposes. Similar considerations may apply to other uses of material, including performance in the classroom, and transmission by electronic means, including via the internet. In some cases, such as classroom performance of sound recordings and videos, additional exceptions are specifically provided by the legislation.

Step One: Is the material you seek to copy protected by copyright and owned by a third party?

Material that is in the public domain (this will be the case if all of the authors of a published work died more than 50 years ago) will no longer be subject to copyright protection. Care must be taken to consider the work itself, since if it contains new material, for example, it might be subject to copyright. In general, it is assumed that most of the material used in University of Toronto teaching and research is subject to copyright.

If no > you may copy and use the material without seeking permission

If yes > proceed to Step Two

Step Two: Does the University already have permission to copy the material under an existing licence with the publisher of the work, either directly or through Access Copyright?

The University has entered into licences with large numbers of publishers, both directly and through Access Copyright, which allow University faculty, staff and students to copy certain works, subject to the terms and conditions of the particular licence. Information about licences is available through the library and the subject will also be discussed in updated Copyright FAQs that will be issued as soon as possible. If the material is licensed,

3

and your proposed use falls within the scope of what is permitted by the licence, it is not necessary to inquire further.

If yes > you may copy and use the material in accordance with the licence.

If no > proceed to Step Three

Step Three: is the copying you propose to do “substantial”?

Copyright in section 3 of the Act includes the sole right to reproduce the work “or a substantial part thereof.” Copying that is not substantial does not require permission or payment and no further analysis is required.

As you would expect, what is considered “substantial” is a matter of degree and context. A small amount copied from a much larger work will often not be viewed as substantial depending on the nature of the work, and the proportion of what is copied to the underlying work as a whole. The analysis is not purely quantitative: even a relatively short passage may be viewed as substantial in some circumstances, especially if it is of particular importance to the original work.

The “short excerpt” criteria set out below in the discussion of fair dealing assume that, even though short, the excerpt constitutes a substantial part of the work when viewed in context. Please note that, although not a copyright concept, copying of parts of a work, even if not substantial, will typically require appropriate citation of the source, depending on academic conventions.

If no > you may copy and use the material without seeking permission

If yes > proceed to Step Four

Step Four: is the copying permitted by “fair dealing” or any of the other exceptions to copyright?

Although fair dealing is an exception to copyright, the courts have made clear that it is a “user’s right” and is not to be narrowly or restrictively construed in the research, private study, educational or any other applicable context. Indeed, the Supreme Court has said that it should be given a “large and liberal interpretation.” In its recent decision dealing with the K-12 context, the Court noted that teachers are there to facilitate the research and private study of students, that their activities cannot be viewed as completely separate from such research and private study and, indeed, that their activities are symbiotic with those of their students. Although the Court has not ruled on the post-secondary context, one could argue that there are many similarities at that level and that the concept of fair dealing as a user’s right should likewise expand at the university level. Recent amendments to the Copyright Act which added educational use as a specific allowable purpose under the fair dealing exception will also likely expand the availability of fair dealing in the university setting.

4

To qualify for fair dealing, two broad tests must be passed.

First, the « dealing » must be for an allowable purpose. The activity must be for one or more of the specific allowable purposes recognized by the Copyright Act: research, private study, education, parody, satire, criticism, review, or news reporting. Use of a copyright-protected work for teaching or research will typically pass the first test.

Secondly, the “dealing” must be « fair. » In its landmark CCH decision in 2004, the Supreme Court of Canada identified six factors that are relevant in determining whether or not the dealing is fair. In 2012, the Supreme Court elaborated on the interpretation and application of those factors in the context of K-12 educational institutions, and that elaboration will doubtless influence the application of the six factors in the post-secondary context as well. The six factors are (in abbreviated form – for the Court’s full commentary see paragraphs 54 to 60 of CCH: via this link to the CanLII database http://canlii.ca/en/ca/scc/doc/2004/2004scc13/2004scc13.html ):

1. The purpose of the dealing

2. The character of the dealing

3. The amount of the dealing

4. The nature of the work

5. Available alternatives to the dealing

6. The effect of the dealing on the work

The relevance of the factors depends on the context. Sometimes, certain factors will be much more significant than the others. Occasionally other factors, beyond these six, may be relevant. It is not necessarily the case that all six factors need to be satisfied.

Even if the copying does not constitute fair dealing, it may be permitted under one of the exceptions in the Act that are specific to educational institutions, such as classroom performance of music, sound recordings and videos. The University’s Copyright FAQs document, when updated and re-published, will provide further practical guidance as to whether a specific exception applies to your activity.

If yes > you may copy and use the material without seeking permission, and, if you are using a specific exception, subject to the conditions or limitations that apply to that exception.

If no > you need permission to copy and use the material and should contact the Library for more information and guidance.

5

B) Guidelines as to what constitutes “fair dealing”:

The University of Toronto believes that these Fair Dealing Guidelines provide reasonable safeguards for the owners of copyright-protected works in accordance with the Copyright Act and the Supreme Court decisions, and that they also provide a good sense of the extent of copying that the University of Toronto views as likely to be considered fair dealing in most contexts – all with the understanding that there may be additional scope for fair dealing in the University setting but that these will require some guidance from a knowledgeable expert at the University.

The following points assume that 1) the copying is of a copyright-protected work; 2) an available University licence does not cover the work; and 3) the copying is of a “substantial part” of the work. Further, they only deal with situations where fair dealing needs to be considered, and not with specific exceptions such as classroom use of video, or the creation and dissemination of user-generated content, which have separate statutory requirements but may be available even if fair dealing is not.

1. Faculty and other members of the teaching staff, as well as other University staff supporting the educational activity may communicate and reproduce, or otherwise deal with, in paper or electronic form, short excerpts (as defined below) from a copyright-protected work (including literary works, musical scores, sound recordings and audio-visual works) for the purposes of research, private study, education, parody, satire, criticism, review, or news reporting

In some limited circumstances, such as with a photograph or drawing, an entire work may be copied.

2. Copying or communicating short excerpts from a copyright-protected work for the purpose of news reporting, criticism or review must mention the source and, if given in the source, the name of the author or creator of the work.

3. Subject always to the consideration and application of the fair dealing factors referred to above, a copy of a “short excerpt” from a copyright-protected work may be provided or communicated to each student enrolled in a class or course:

a. as a class handout

b. as a posting to a learning or course management system that is password protected or otherwise restricted to students of the University

c. as part of a course pack

6

4. A “short excerpt” can mean (but is not limited to and may vary depending on the exact nature of the work being used, and of the use itself, all in the context of consideration and application of the fair dealing factors):

a. up to 10% of a copyright-protected work (including a literary work, musical score, sound recording, and an audiovisual work)

b. one chapter from a book

c. a single article from a periodical

d. an entire artistic work (including a painting, print, photograph, diagram, drawing, map, chart, and plan) from a copyright-protected work containing other artistic works

e. an entire newspaper article or page

f. an entire single poem or musical score from a copyright-protected work containing other poems or musical scores

g. an entire entry from an encyclopedia, annotated bibliography, dictionary or similar reference work, provided that in each case you copy no more of the work than you need to in order to achieve the allowable purpose.

5. Copying or communicating multiple different short excerpts from the same copyright-protected work, with the intention of copying or communicating substantially the entire work, will generally not be considered fair dealing.

6. Copying or communicating that exceeds the limits in these Fair Dealing Guidelines will require further analysis, including additional scrutiny of the principles enunciated in CCH and the other Supreme Court cases referred to above. If you find yourself in this situation you should seek guidance from a supervisor or other person designated by the University for evaluation. An evaluation of whether the proposed copying or communication is permitted under fair dealing will be made based on all relevant circumstances.

7. Any fee charged by the University for communicating or copying a short excerpt from a copyright-protected work must be intended only to cover the University’s costs, including overhead costs.

November, 2012

University of Toronto

Il est intéressant de noter leur approche, qui tente de poser des questions simples pour isoler la situation juridique d’un usage.